About halfway through its new documentary ”Life after” Director Reid Davenport announces, “This film is not about suicide. “It is a statement that contravenes the simplest a logline for Sundance Premiere, who would say that the project is an exploration of assisted suicide in disabled people.

In the middle of the study is the story of Elizabeth Bouvia, whose case became a national sensation in the 80s. But as Davenport formulates both in his statement referred to above and throughout his passionate and convincing film, the question is whether the disabled deserves the right to die also a matter if they have the ability to live.

Davenport himself speaks from an experience site, which makes him uniquely positioned to tell this story. He himself has cerebral palsy and won Independent spirit true than fiction award For his first function, 2022’s “I didn’t see you there,” that digs into the traditions of freak -show to spin a deeply personal story. In “Life After”, Davenport both challenges the ability of the audience about the lives of disabled people, and increases expectations of how documentaries should develop.

The film opens with archive films by Elizabeth Bouvia that pops up in court. You can see why Bouvia’s saga immediately appealed to the media. Like a headline noted at that time: she was young, beautiful and wanted to die. (Mike Wallace followed her for several years; Davenport calls him “scary.”) Born with cerebral palsy, bouvia, with high cheekbones and shaped eyebrows, argued in front of a court in Riverside, California that she could starve herself to death on a Local hospital. She lost the case.

What first fascinated Davenport about Bouvia’s story is that when he researched her he could not find any evidence that she had actually died all these years later. But “Life After” is no simple investigation to find this woman, even though Davenport works with philosophy to know what happened to her during the years after public frenzy would be the key to understanding her. More importantly, it is an expansive look at what it means when the disabled is told that they have the right to die.

Bouvia is just a character in this story. Another is Michal Kaliszan, a man in Canada who lost his mother, his primary caretaker, and considered dying through the country’s maid (Medical Assistance in Dying) program. Even if he works, the cost of full -time care would be too much, and the only other option would be to go to a facility that feels like a prison.

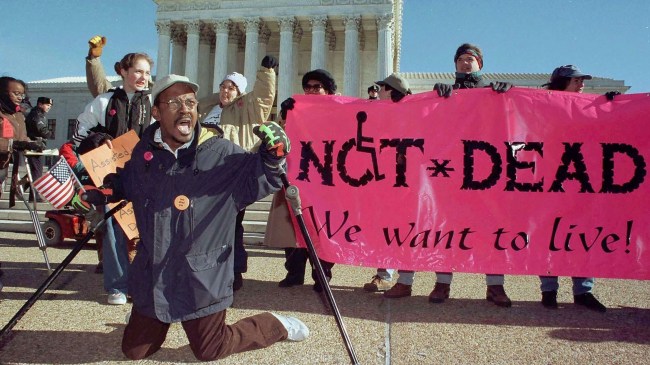

But while the film begins with an empathy for why people may want to die, it slowly begins to reveal the systematic failures that make those with disabilities believe that it is their only alternative. By structuring the story in this way, Davenport Slurly challenges the supposedly good liberal decision on assisted suicide as a compassion. What begins as a slow execution of assumptions ultimately ends up a complete condemnation of systems that would rather have disabled people to die than invest in the health care required to improve their lives.

Canada’s embrace of maid is at the center of Davenport’s case, with the statistics that the government’s heartfelt embrace of the program has resulted in a form of eugenics. He also weaves in the story of Michael Hickson, a man paralyzed with a brain injury that was not treated for Covid at an Austin hospital. His wife, Melissa, heartbroken and angry with her loss, gives some of the most moving testimonies.

Davenport is solely focused on the subject of suicide when it comes to disability. He is not interested in diving into what is concerned with terminal illness at all. For anyone who claims that it makes “life after” one -sided, Davenport’s own voice gives a furious equivalent to it. Davenport is considered in how he puts himself on the screen. His move against Elizabeth’s story is that he sees himself in her, but he also lets his subjects tell his stories without interruption. Sometimes during the interviews you see his curly hair bobbing on the side of the screen, a reminder of his interested interest. That framing is sometimes cinematic, but it is thematically potent.

At the same time, Davenport wants to remind his viewers that if he had not had the opportunity for him, he can choose to die as well. It is a feeling that is crystallized when filling in the maid application. That he can direct “life after” supports his theory that when people are given proper care, they can thrive.

And he always takes his story back to Bouvia, who faces everything. Since the film begins with this question of what happened to her, it seems like a spoiler to reveal what Davenport reveals. However, it is safe to say that what Davenport thinks is surprising and complicated.

What Davenport says is true: This movie is not about suicide, which would mean it would be about death. Rather, it is about life, life that is much more complicated than soundbite clips from the past can give.

Rating: A-

“Life After” premiered at the Sundance Film Festival 2025. It is currently seeking US distribution.

Want to keep you updated on IndieWire’s movie Reviews And critical thoughts? Subscribe here To our recently launched newsletter, in review by David Ehrlich, where our main film critic and manager Reviews The editor rounds off the best new reviews and streaming elections along with some exclusive Musings – all only available for subscribers.