“Why don’t you have a seat over here.”

It is perverse that a TV news program about children predator quickly developed his own catchphrase, as if silver-throated host Chris Hansen was just another incarnation of Steve Urkel, but such was addictive mix of shocking docudrama and lizard-brain entertainment that defined “Dateline NBC” spinoff “To Catch a Predator.”

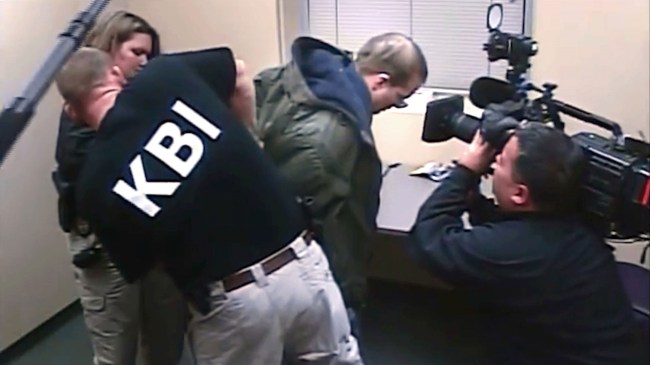

On the air from 2004 to 2007, the show followed a simple formula: Members of a volunteer organization known as “Perverted-Justice” would find men online and lure them to a house with the express promise of having sex with a minor. When the marks arrived, they were met by a young-looking decoy – only for Hansen to step out of the shadows moments later, accompanied by a camera crew ready to broadcast his shame to the world. After gushing apologies and pleas for mercy as Hansen read aloud from transcripts of their online chat logs, the predators were told they were “free to go.” In the later seasons of the show, some of these unsuspecting guest stars must have known that a bunch of local cops were waiting to deal with them the moment they stepped out.

Backstopped by the sheer horror of the crimes its subjects intended to commit against children, “To Catch a Predator” effectively turned an unspeakable act into a public spectacle. It didn’t seem to matter that the show made the vast majority of these cases impossible to prosecute, or that the filming threatened to blur the lines between entertainment media and law enforcement even more than “Cops” already had; people reveled in the sheer reality and gratification of seeing a bad guy’s life end before their eyes, and few would argue that the predators caught in Hansen’s trap deserved a much different fate. In part, it is because these men intended to do such terrible things. And in part, that’s because “pedophile” is a word that has the power to make even the hint of nuance seem unforgivably immoral (which helps explain its prominent use as a political weapon).

A raw and captivating documentary that skeptically reconsiders the program’s appeal, legacy and ethics, David Osit’s “Predators” certainly does not make the case that Hansen’s marks were innocent bystanders trapped against their will. On the contrary film opens with the skin-crawling audio of a phone call between a 37-year-old predator and one of the “13-year-old” Perverted-Justice decoys, and that alone is enough to establish the undeniable secret of what was at effort with these sting operations.

And yet, as both a filmmaker whose work (“Mayor,” “Thanks for Playing”) has always been compelled by moral inquiry, like a person for whom “To Catch a Predator” triggered a whirlwind of conflicting emotions, Osit is haunted by his enjoyment of a show that was ultimately less interested in crime than punishment Hansen’s theater helped pave the way for a media landscape fueled by humiliation rituals, and “Predators” benefits from the success of that NBC show — along with the tragedy of how it ended, and the YouTube watchers who have iterated on its format with even less oversight than Hansen ever had — in an investigative investigation of its own.

The film’s conclusion is clear from the start: “To Catch a Predator” was an invitation to see the world in black and white, a perspective that has only become more enticing in light of America’s subsequent turmoil. It was an invitation to tar and feather people so clearly “evil” that anyone watching at home couldn’t help but feel “good” by comparison. And while it sold itself as an invitation to understand an inexplicable wrong, the show’s power was rooted in the permission it gave us to ignore why such heinous violations continue to happen.

To paraphrase the Scandinavian ethnographer Osit interviews throughout the film: Chris Hansen might ask his targets to “help me understand” why they prey on children, but the appeal of shows like “To Catch a Predator” depends on not understand their subjects. “If you show these men as people,” says the interviewer, “the show breaks down.” Still active today, Hansen has now been staging these sting operations for more than 20 years, and yet he’s no closer to knowing why some men can’t stop themselves from falling into his traps.

The telling admission doesn’t come until the film’s third act, when Hansen agrees to a sit-down interview that frames the former “To Catch a Predator” host as if he were one of the show’s unsuspecting marks. First, Osit catches up with some of Hansen’s ex-collaborators, whose unresolved feelings about the experience complicate the show’s reputation as a moral crusade. One of the decoys Osit interviews smiles at the camera as she fondly recalls her days as an actress, but her discomfort grows as she is forced to answer questions she never dared to ask herself. Another is more clearly traumatized by his involvement in the show, especially because he was cast in the episode that ended with a man killing himself when the camera crew entered his house. A law enforcement official refers to his participation as “a stain on my soul.”

“Predators” makes sure to hear from some contestants who are proud of their work on the show (or other shows like it), most notably a Kentucky DA who feels like he came straight out of “The Dukes of Hazzard,” and insists that his job was only to catch predators, not to rehabilitate them. Most of these people serve to reinforce dehumanization at work, none more so than the police officer who responded to the aforementioned suicide, and – in footage from the day – can be seen laughing at the dead before his body has even been removed from the house.

Asking for empathy for predators would be a highly topical act for any documentary filmmaker, but Osit is less interested in bringing Hansen’s targets to justice than he is in interrogating our desire to act as judge, jury and executioner. (I’m not sure if that explains why he doesn’t interview any members of Perverted-Justice, or if it makes their absence seem all the more glaring.) Split into three parts that reflect an endless pattern of crime, punishment, and cultural relapse , “Predators” fixates on our shared complicity in perpetuating that cycle with every click.

The middle part of the film introduces us to “Skeet Hansen,” among the highest profile of the many Chris Hansen impersonators who have found success on YouTube, and it’s immediately clear that the guy is doing his namesake no favors. Bumpy and unpolished where OG Hansen was smoother than a used car salesman, Skeet’s drift only serves to underscore how transparently “To Catch a Predator” exploited the worst crimes imaginable for cheap entertainment.

And Skeet at least has the decency to call the police on his targets when he’s done with them – so many of the amateur predators you can find online today prefer to attack their targets in public and leave them for dead when the content is uploaded to Twitter and TikTok. As damned as Skeet’s appearance may be, Osit convincingly argues that everyone who watches his videos is equally complicit in perpetuating the cycle.

To that point, the most enlightening part of the film’s middle chapter is the light it shines on the victims of childhood sexual abuse, and how some of them – perhaps more than others – can play an active role in perpetuating the false binary of good and evil. Skeet’s most enthusiastic collaborator is revealed to be a survivor, and the nonchalant testimony she gives here expresses why people like her might be particularly anxious to see predators strung out in a virtual square: it’s not just out of revenge, but because such the cause and effect of crime and punishment enables her to understand a trauma that must be all the more painful to endure without an explanation.

At least that’s how Osit sees it. The director has asked critics to discuss the third act of his film with discretion, but it’s safe to say that “Predators” stems from a personal need for catharsis. Like the show it scrutinizes, Osit’s documentary mines “content” from heinous crime, but it does so for radically different purposes. Osit is no more qualified to – or interested in – “solving” the epidemic of child predators than Chris Hansen ever was, but he is clearly troubled by the fact that Hansen and his imitators depend about hindering our ability to meaningfully manage this crisis. If anything, their work exists to promote it and to inflate the public’s impression of how widespread the crisis really is.

Did “To Catch a Predator” save a small number of children from being abused? Possibly. Probablyeven. And even a would be reason enough to celebrate it for that. But, like so much of the media that has been created and consumed in the 21st century, the show did so because of its own insistent desire to exist, and its success depended on simplifying a world that continues to grow more complicated by the day; on eroding nuances, problematizing sensibilities, and mulching genuine concern into unrepentant bloodlust.

As “Predator” makes clear in a heartbreaking page about an 18-year-old high school freshman whose life is ruined after Hansen learns he’s dating a younger classmate (the age difference between them is legal in several other states), there are very real consequences to portraying dehumanization as a righteous act of public justice. “To Catch a Predator” might seem the wrong lens to make this case, as few people invite less sympathy than the men who found their way into Hansen’s web. But that is precisely what makes Osit’s film such a powerful indictment of the lens through which we have since been conditioned to see everything else as well.

Grade: B+

“Predators” premiered in 2025 Sundance Film festival. It is currently seeking distribution in the United States.

Want to keep you updated on IndieWire’s film reviews and critical thoughts? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, where our chief film critic and chief reviews editor gathers the best new reviews and streaming picks along with some exclusive musings—all available only to subscribers.