Terrible things happen to people every day: War is raging, good people are betrayed, disgusting governments conspire and innocent are left to understand everything. When “My father and qaddafi“Filmmaker Jihan K asks his uncle if they will ever know the real details about what happened to her father, the Libyan politician Mansur Rashid Kikhia, he seems confused, see his beloved cousin death as just a drop in a sea of tragedy. He tells the filmmaker” the country himself.

But for the filmmaker and her family, answers are needed. It is not to know that it is so painful. Who kidnapped his father? Under what circumstances? Was he imprisoned or murdered or both, and will they ever have a grave side to visit?

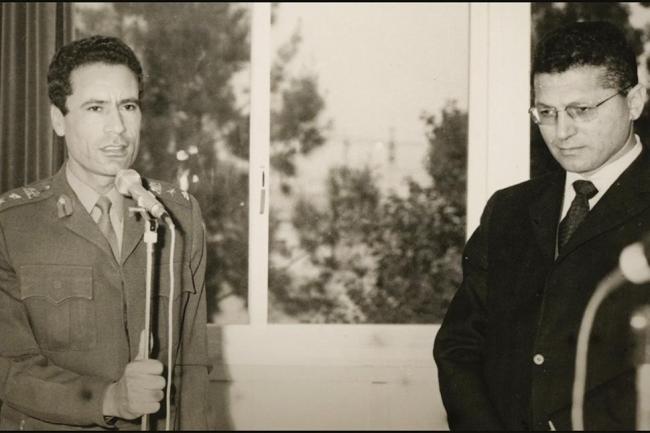

Jihan’s astonishing documentary is proof of an astonishing man; It is the work of a talented young filmmaker who picked up a camera at an early age to speak his missing father back to existence. “My father and qaddafi“Maps the story of Libya’s previous century with a clear view of one of its most public tragedies: 1993-remarks by the former Libyan ambassador turned opposition leader Mansur Rashid Kikhia from a human rights conference at a Kairo hotel, knowledge of and the responsibility that was denied by both self-authorities. done this extraordinary film To fight with what happened to her father, she has no memories about – and the beloved country they shared.

It may be a bit to feel optimistic about as the film, in its central actions, kinetically maps Libya’s history and its resistance patterns: semi -remembered genocide, colonization and a post –Arab feather Civil war that has seen much of the country lie in ruins. Fates for so many were decided on the 1969 day when a dashing and unfortunately underestimated the 25-year-old Colonel Qaddafi Grapped power from the monarchy in a few hours and promised a new golden era, inspired by Egypt President Nasser.

Libya’s history does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes, every generation of nostalgic for the good old days that preceded them, paper over its brutality. In the present even the survivors longing for the survivors to return to the Qaddafi regime and say: “Now it is even worse than with Qaddafi. Then we had a dictator, now we have 1000.” But even with his tyranny in the latest memory, it is still remarkable to see what a insignificant end this once pompous and the previous man would eventually face: killed by the people he oppressed, pulled through the streets with his bloody corpse, then stored in a restaurant cooler where people would stand in line and even with his children to catch their children.

Jihan’s mother, whose insight and dignity cannot be overestimated, offers a measured answer: that despite what she and her family have gone through, she cannot “celebrate death.” She is the film’s most convincing and enchanting voice, and although it is difficult to understand how her handsome husband – she would appreciate that I pointed out, as she often does, how handsome he is – could risk leaving her a single mother, she insists that his kidnapping turned her from a normal woman and into a powerful “sword. Although it is deeply tragic that this family lost a parent who stood up to his struggle for the ordinary man, the one who remained is equally formidable.

More than just a portrait of Kikhia’s fascinating life, his daughter’s film offers a delicious portrayal of both longing and the complexity of the grief process. In each frame, Jihan longs for not only knowing what happened to her father, but also to know her father at all. Her loving older brother can remember the feelings he had when his father was present, but for her, instead of some memories, she has only photographs, newspaper clips and the odd pictures (where he is always impeccable showed and often seen revealing in the joy of paternity).

Jihan comrades on these pictures, and now recognize some of them that her father seems busy, as if he is already aware of the tragic fate that would suffer from him. She also claims with the knowledge he knew and accepted the risks of his trip to Cairo, and how it could potentially leave her to grow up fatherless. But as her mother puts it, “death is one, but the ways you die are many,” and her father stood up for the Libyan’s life despite the horror he was conscious could lie in front.

For all its formal elegance, “My Father and Qaddafi” are also exciting. Many answers to questions that at first seem meaningless to persecute are eventually solved and their answers puncture the film’s devastating final act, which hits as a place in the heart, as the solutions are completely grotesque and begging the question whether may not know would have been a kindness to these already besieged people. But there is a balance here, and the sorrow of the film is mercifully punctured by joy: home video films of piano practice, by Jihan’s mother brilliantly when reminding a prison with a (handsome) powerful man who believed in her artistic talent and of a Thanksgiving where Jihan’s older sibling -washed to be to be.

In total, Jihan’s film is both an act of reminder and resistance that is written great. In a world where decency may feel meaningless, “my father and Qaddafi” present a story that forces you to be decent anyway. We see a man who refuses to accept that his countrymen live their lives in oppression, a woman who refuses to let her husband’s victim brushed aside by troublesome forces, and a young filmmaker who refuses to let her father’s story are controlled by those who did not love him. It is a truly inspiring work and a credit to Jihan who, even with such a personal subject, she can convey both micro and macro efforts. Terrible things happen in this movie, just as terrible things continue to happen in the places that Mansur Rashid Kikhia kept so dear, but we must, as he did, somehow find the strength to resist.

Rating: A-

“My father and Qaddafi” premiered at 2025 Venice Film festival. It is looking for US distribution.

Want to keep you updated on IndieWire’s movie Reviews And critical thoughts? Subscribe here To our recently launched newsletter, in review by David Ehrlich, where our main film critic and Head Review’s editor rounds off the best new reviews and streaming choices along with some exclusive Musings – all only available for subscribers.